UK banking officials and pension fund managers have expressed concern about the potential market failure of long-term government Bond auctions, which could plunge the country into financial turmoil similar to that which followed the 2022 mini-budget.

Market Failure: A Dire Warning for the Treasury

The UK’s Debt Management Office (DMO), together with the Bank of England, recently held serious discussions with key figures from the banking and pension sectors. The core of these discussions was a clear warning: the UK is perilously close to its first failed debt auction in over a decade. The crux of the issue is the expected mismatch between supply and demand for long-term public debt with maturities in excess of 20 years.

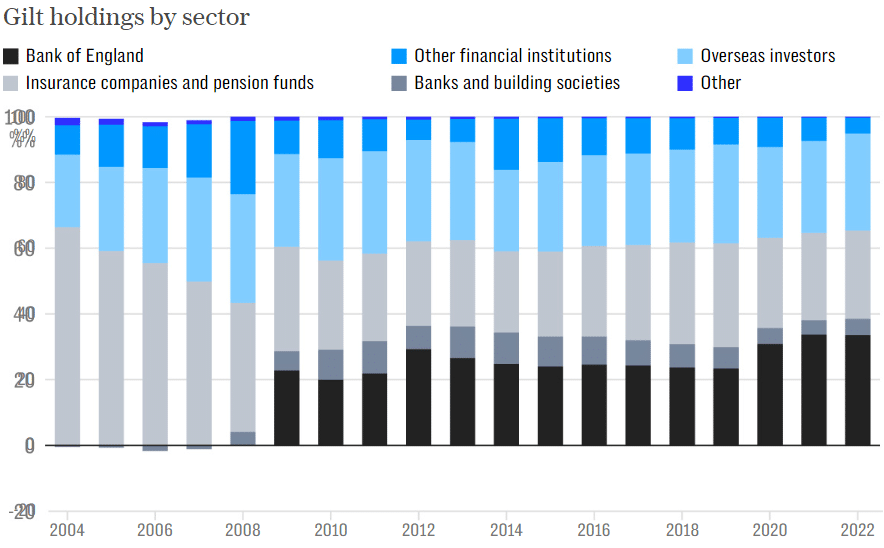

Moreover, ambitious government debt issuance plans, coupled with a transformative shift in the pension market, are likely to exacerbate this imbalance. In particular, the shift from traditional pension schemes to those linked to market performance is turning former buyers into potential sellers of long-term debt.

To mitigate these risks, UK authorities have made significant adjustments to their debt issuance strategy. Most notably, the planned volume of long-dated debt issuance has been scaled back more than originally anticipated. The DMO now plans to issue £53bn and £49bn in the current and subsequent financial years respectively, despite an increase in total bond issuance.

These adjustments are strategically focused to better align with market demand dynamics and reflect a keen awareness of the need to avoid the pitfalls of past financial disruptions.

Regardless of these measures, voices within the country are sceptical about their effectiveness in averting future market disruption. The fundamental issue of supply and demand mismatch remains a concern that some believe has not been adequately addressed by the recent changes.

Although seemingly a minor disruption, the potential of a failed auction carries the risk of triggering a wider crisis of confidence in the government’s ability to manage its finances. An event like this could cause instability similar to what was caused by the 2022 mini-budget. This highlights the importance of careful financial management.

The possibility of an auction failing is not uncommon. The most recent failed auction occurred in 2009, in the wake of the financial crisis, when the Debt Management Office (DMO) attracted just £1.62bn of bids for a sale of £1.75bn of 40-year bonds.

Experts in the field have expressed concern about falling demand for long-term debt. Imogen Bachra, a senior rates strategist at NatWest, believes that the Debt Management Office (DMO) is likely to be cautious to avert the risk of a failed auction. She shares the industry-wide apprehension.

“I think the risk is more that the long end remains quite cheap because all of that supply is coming against the backdrop of changed demand at the long end. The DMO has long been able to rely on pension funds to absorb all of its issuance, essentially. I think that’s different now.” – Imogen Bachra

Pension Industry Shifts

Another crucial element in this story is the changing pension industry landscape. The progressive closure of defined benefit (DB) schemes, which have traditionally been strong purchasers of long-term gilts, represents a shift towards investment strategies that are more dependent on market performance. This shift, while in line with wider industry trends, presents specific challenges for gilt demand.

As insurance companies take over responsibility for these pension funds during the ‘buyout’ phase, they are subject to different regulatory requirements, which could lead to a reduction in gilt holdings. Together with the Bank of England’s own gilt offloading activities, this transition adds another layer of complexity to the market’s supply/demand balance.

Bank of England’s Contribution

Alongside the changing landscape of the pension industry, the Bank of England continues to offload long-term debt at a rate of around £2 billion per quarter, increasing supply. Despite strong demand for UK debt in recent months, there could be less demand for long-term debt as pension funds continue to reduce their risk, which could lead to a shortage of debt.