The affordability of housing in Australia continues to be a significant challenge for many. The gap between skyrocketing property prices and stagnant wages has made homeownership increasingly difficult for average Australians.

While it is rare for property experts to discuss falling house prices as a potential solution to this crisis, Eliza Owen, head of research at Cotality (formerly CoreLogic), has offered a compelling argument for why a price correction might be necessary.

Owen, who leads one of the country’s most trusted real estate data providers, critiques the prevailing stance of political leaders like Clare O’Neil and Michael Sukkar, who continue to favor rising house prices.

According to ABC News, both spokespeople have stated that they would prefer house prices to increase, but at a slower rate than wages. However, Owen contends that this approach will only deepen the affordability crisis. Instead, she argues that falling prices are essential to restoring housing accessibility.

Rising incomes are not enough

One key factor affecting housing affordability in Australia is the gap between house prices and wages. As house prices reach unprecedented levels relative to incomes, it would take decades to bring prices in line with the average income.

This has been highlighted in recent analyses, including one by Tarric Brooker, which illustrates the widening gap.

The current “housing affordability” policies proposed by both major political parties, while offering some relief to first-time buyers, are not likely to resolve the root problem. Labor’s policy aims to ease deposit requirements, while the Coalition’s plan includes tax incentives and access to superannuation for home deposits.

Owen contends that such measures will only fuel further price increases, rather than addressing the affordability crisis. As she warns,

The alternative — runaway prices, deepening inequality, and falling ownership rates — could prove more damaging in the long run – She adds that

As a nation, we can’t keep kicking the can down the road on housing affordability.”

Is Australia ready for falling prices?

Despite concerns about the economic impact of falling house prices, Owen argues that Australia can afford a price correction. She notes that most homeowners are well-insulated from price declines due to the significant increase in home values over the past decade.

In fact, according to CoreLogic’s data, 95.7% of residential resales in the December 2024 quarter resulted in a profit, with many homeowners still seeing substantial gains. Even with a 10% reduction in house prices, the majority of vendors would still profit, with the median profit sitting at $263,000.

Furthermore, for prospective first-time buyers, a 10% price decline would reduce the median deposit requirement by $16,000, making homeownership more attainable. As Owen points out,

if resale values were reduced by 10 per cent, 88.5 per cent of vendors would still have recorded a gain, with the median profit sitting at $263,000.

The broader economic implications

While price falls could benefit individual buyers, there are concerns about the broader economic impact.

The real estate and construction sectors make up a significant portion of Australia’s economic activity, and a sharp downturn in house prices could lead to job losses in these industries.

The Property Council estimates that 1.4 million full-time jobs are directly linked to the property sector, with an additional 1.75 million jobs indirectly supported by the sector.

However, Owen argues that a housing downturn need not be viewed as a disaster for the economy.

She explains that

housing is not only an investment, but also something people consume.

If housing costs were lower relative to incomes, Australians could potentially redirect spending to other areas such as health, education, and technology, which could stimulate other sectors of the economy and improve overall quality of life.

Owen further emphasizes that a price correction could result in greater overall benefits :

If housing costs were lower relative to income, Australians could redirect more spending to health, education, and technology, potentially even increasing earning potential as a result.

Lessons from history

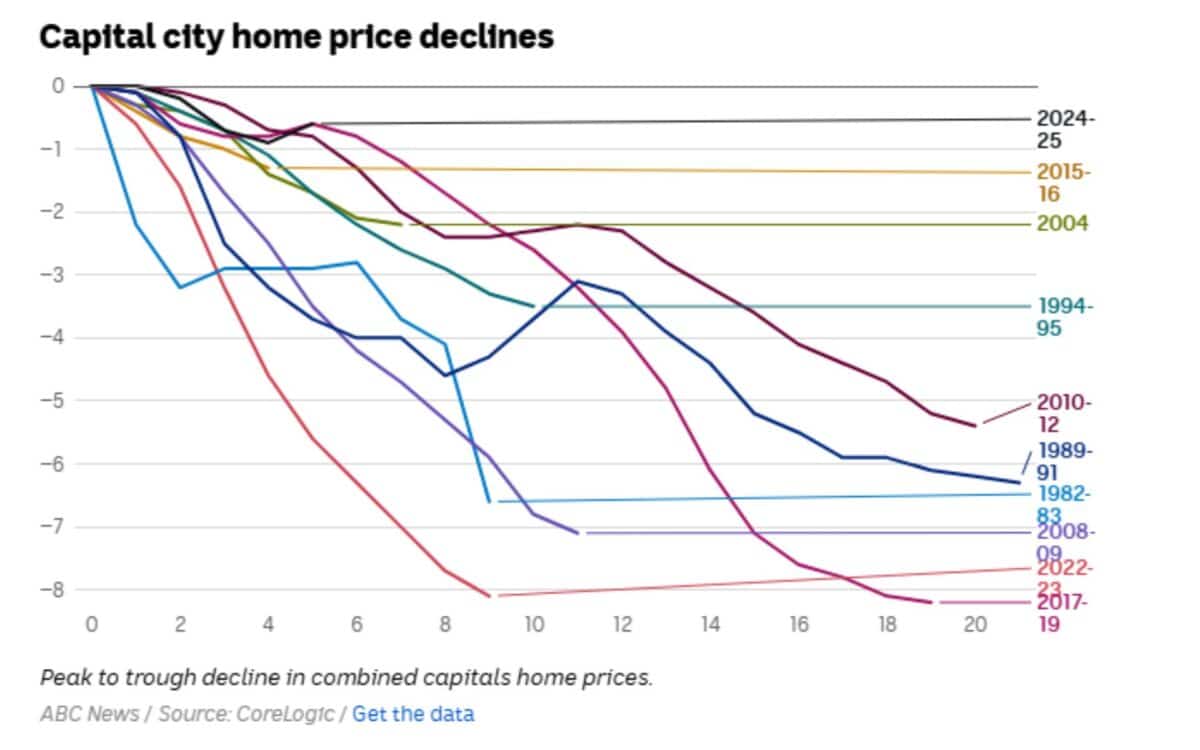

Australia has weathered housing downturns before. For example, between 2017 and 2019, home prices fell by 8.2% due to stricter lending rules.

In Western Australia, a post-mining boom slump saw prices fall by 16.1% between 2014 and 2019, but mortgage arrears remained low, and the financial system remained stable.

These examples demonstrate that price corrections can occur without triggering widespread financial distress, provided that lending standards remain strong and borrowers are well-prepared. As Owen notes,

By mid-2020, nearly 44 per cent of home resales in Perth were made at a nominal loss. Yet despite this prolonged downturn, mortgage arrears remained below 2 per cent, and the financial system remained stable.

This highlights how price corrections can happen without significant risks, given that borrowers are well-positioned.